Friday, August 12, 2005

Broadband comes to the North

| The Ottawa Citizen |

August 11, 2005

Tucked into a jagged glacier carved fiord off the aquatic rich Cumberland Sound in southeastern Baffin Island, the village of Pangnirtung, population 1,276, is nestled on a tundra flat flanked by majestic granite mountains towering up to 1,000 metres. It seems like one of the most remote communities on earth.

But the large satellite dish on the picturesque hamlet's western shore symbolizes a very different scenario. Newly connected state-of-the-art 2.5 GHz wireless broadband technology provides Pangnirtung and 24 other fly-in communities in Nunavut, who are connected to a network called QINIQ -- named after the Inuktituk root word for search -- with vital high-speed Internet access to the outside world and to each other.

The residents of Pangnirtung (which means "place of the bull caribou'') are excited about the effect high-speed broadband access might have on their personal and business lives. Mika Etooangat, 21, has already noticed several significant improvements over dial-up access. "I can download music a lot quicker, and it's great for instant e-mail and chatting with friends. Before when I used dial-up, it was not only slower but would sometimes disconnect on its own,'' says the assistant senior administrative officer of the Pangnirtung Hamlet Office & People's Community Centre.

Peter Wilson, general manager of the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts, which sells Inuit artifacts around the world, including soapstone carvings, prints, and tapestries, is bullish on the potential economic advantages broadband access to the Internet will present. He plans to have an e-commerce website up and running before the end of the year. And he's also looking at broadband-enabled, voice over Internet protocol telephony.

"Long-distance telephone charges for business are so high here. But with voice over IP, we could end up paying a lower fee and, if all is working well, have better sound quality, too. That's a real important way broadband can improve business telecommunications not just in Pangnirtung, but throughout Nunavut as well,'' he says.

Donna Copeland, manager of the town's Auyuittuq Lodge, also has dreams for broadband access. Her lodge houses many of the region's backpackers before and after their trek through the pristine Auyuittuq National Park (translation -- "the land that never melts''), site of the 5,100 square-kilometre Penny Ice Pack glacier and many of Nunavut's highest mountain peaks. She'd like to have the service available for cruise ship passengers -- seven ships will visit Pangnirtung this summer, for instance -- to be able to come into her motel and get quick access to their office and personal e-mail.

Copeland already enjoys broadband Internet access personally, calling it a "godsend'' in part because it features speed "that is just phenomenal.'' The 19-year resident of Pangnirtung signed up for a broadband connection in her home at the first opportunity last winter when she volunteered to sample one of the new modems, several months before they went live to the rest of the hamlet.

She became an instant convert. "Dial-up served a purpose, but now that I can compare the two, there's really no comparison,'' Copeland says. "Broadband offers the power and speed I need to complete my transactions.''

The fact wireless broadband access has been deployed across Nunavut at all is, in and of itself, a magnificent technological feat. At 1.994 million square kilometres, Canada's newest territory occupies one-fifth of Canada's total area. But it is isolated. Only about 30,000 people inhabit this vast, mostly pristine space, whose largely treeless landscape sparks to life in the perpetual light of summer, sporting brilliant hues of tiny purple and yellow flowers like Purple saxifrage and Arctic poppies on its hillsides.

The population is dispersed over 25 communities and three time zones. Approximately 7,000 live in the capital Iqaluit (meaning "place of many fish''), near the southern end of Baffin Island.

Travel from one community to the next is usually only possible by air. Some ports also have a limited shipping season (generally from July to October in the Eastern Arctic). Only two communities -- Arctic Bay and Nanisivik, some 20 kilometres apart at the northern end of Baffin Island -- are connected by road.

How then, did wireless broadband Internet access become a territorial-wide reality?

One of the early visionairies was Adamee Itorcheak, who founded a small Internet Service Provider company named Nunanet Worldwide Communications Inc. in August 1995. "Adamee has worked tirelessly not just for Iqaluit, but all Nunavut access, for so long,'' says Lorraine Thomas, secretary-treasurer of the Nunavut Broadband Development Corporation. "Adamee had a vision of this wireless connectivity scenario in the late 1990s when nobody else had a clue about it, and he has devoted a lot of his energy, time and money into it.''

Itorcheak, a native of Iqaluit who in 2001 was named to the National Broadband Task Force, painstakingly built his business to help give Nunavut's capital city a leg up on technology when the new Territory officially came into being on April 1, 1999. But only 10 other communities in Nunavut at that time had Internet connectivity -- and that was mostly confined to government workers, many of whom heralded from southern Canada.

Despite the efforts of a few pioneering ISPs such as Nunanet, Sakku Arctic Technologies in Rankin Inlet, and PolarNet in Cambridge Bay, there weren't many cost-effective Internet services available to the Inuit people at that time, who comprise about 85 per cent of Nunavut's population. But things began to look up when the federal government signaled its intention of connecting Canada's North to the high-speed information freeway.

Industry Canada announced ia subsidy program in October 2000 (which many believed would have cost at least $1 billion), for the goal of providing all Canadian communities with high-speed broadband access by 2004. This was quietly shelved and replaced by the $105-million Broadband for Rural and Northern Development (BRAND) program in September 2002.

In 2001, the Nunavut Broadband Task Force was established as a local conduit to the National Broadband Task Force so that the fledgling territory's voice could be heard. It made 27 recommendations before completing its mandate, and was succeeded by the not-for-profit Nunavut Broadband Development Corporation (NBDC) in 2003. NBDC's initial job, in part, was to oversee implementation of several key recommendations from the territorial Task Force, including one calling for affordable, easy access to broadband services for residents of all communities, no matter how remote.

"When you actually do the math on how much it costs to put in a satellite infrastructure to, say Grise Fiord (Canada's northernmost settlement, with a population of less than 200 on Ellesmere Island in the High Arctic) versus Iqaluit, then compare that to the number of possible users and divide it on a per-capita cost, no business person would have connected Grise Fiord,'' Thomas points out.

But consistent with the Task Force's recommendation, the project wasn't assessed on a pure business model basis. All communities were connected, and basic broadband subscriptions for all users are now equitably priced at $60 a month across Nunavut. This equality exists in spite of the special challenges and costs that were involved to make high speed access a reality in the most remote communities.

Another major responsibility of NBDC is to ensure that broadband access enhances economic development within Nunavut. One strategy designed to fulfill this is by having community service providers (CSP) located in each of the Territory's 25 venues, thus ensuring some of the subscription revenues stay within the community.

In Pangnirtung, for instance, the Uqqurmiut Inuit Artists Association is the local CSP, represented by Wilson and craft gallery supervisor Jackie Maniapik of the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts. The CSPs in all 25 communities collect a margin of approximately 20 per cent of gross revenue for their endeavours. In return, they assist customers hook up their modems (which requires a downpayment of $150), and act as the initial troubleshooter should any problems occur.

NBDC also tendered bids for a contractor to build both the satellite infrastructure, and provide the so-called "last mile'' hooking up all houses and buildings to the satellite dish within communities. SSI Micro Ltd. of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, was awarded the contract for both those jobs in May 2003.

Although located in the neighbouring territory, SSI Micro had previous experience in Nunavut. In fact, they'd previously built satellite infrastructure in ten communities, including each of Nunavut's three regional capitals -Iqaluit, for the Baffin Region, Rankin Inlet, for Keewatin and Cambridge Bay in Kitikmeot, so those were among the first communities targeted for deployment.

The logistics of laying satellite infrastructure for the other 15 communities posed a number of significant challenges, admits Ryan Walker, manager of the solutions group at SSI Micro. "One of the toughest parts of building these sites was getting the civil work done. The satellite dish is 4.5 metres, so it's got quite a wind load on it, and you need a fairly sturdy foundation to handle that,'' he says.

Moreover, the weather was often a major thorn in the side. Nothing moves in a blizzard, and accommodations are notoriously expensive in Nunavut because of supply and demand, so SSI Micro faced extra costs of about $250/night per person when forced to keep crews weathered in for days at a time.

Even when equipment did move during the construction phase in 2004 and 2005, things didn't always go according to script. "The biggest surprise we had was when our dish for Clyde River showed up in Grise Fiord, which is of course the most inaccessible, furthest away community you can imagine,'' Walker says, adding that it took about one and a half months to charter an airplane to get the extra dish moved to its proper destination.

Improvisation was often the order of the day, too, when smaller communities didn't have all the necessary equipment for installation. In one, SSI Micro's crew had to set up an artificial pulley system using a long gin pole at the end of a loader in order to get the elevation required to put the satellite dish in place.

There was also pressure from the federal government -- as a condition of its $3.885 million in funding -- to complete the project in one year, rather than two as originally planned. To meet the new March 31, 2005 installation deadline, SSI Micro had to order equipment a year earlier in order to ensure it would be aboard the sealift barges in time. There was little or no margin for error given the brief shipping season in the southern Arctic, and even shorter one in the higher latitudes where some communities can only expect one boat a year -- provided the ice breaks up enough to let it through safely.

Today however, with approximately $10 million having been spent to put the infrastructure in place as a resulting of funding from all three levels of government and private business, 2.5 GHz wireless broadband has become a reality across the Territory, with most of the smaller communities having joined the QINIQ network between May and July of this year. Concerns about whether this technological feat could really be pulled off have been replaced by the hopes and dreams of residents across Nunavut.

In Sanikiluaq, a town of about 700 in the Belcher Islands about 165 kilometres west of Quebec in Hudson Bay (territory belonging to Nunavut), Bob McLean, manager of Sanny Internet Services, is the hamlet's CSP. He helped establish a website listing various local artists' carvings, entitled Soapstone Artists of Sanikiluaq, back in 1998. The site subsequently became e-commerce enabled to sell Inuit art over the Internet to clients all over the world. He hopes the new broadband capacity will provide a much more cost-effective and quicker means for customers to transact through that website.

Darrell Ohokannoak is the manager of PolarNet, an ISP based in Cambridge Bay, capital of Nunavut's Kitikmeot Region, located on Victoria Island some 300 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle.

Only about 15 per cent of Cambridge Bay's 1,400 residents are connected to the Internet, but those who've chosen to take advantage of broadband access are "excited it's finally here,'' says Ohokannoak, who also chairs the NBDC board of directors.

Subscribers in the distant northern community are using it in much the same fashion as their counterparts in the south -- online shopping for items like electronics and clothing, online games such as poker, and Internet booked flights, hotels and car rentals for vacations outside Nunavut.

Broadband makes things much easier for members of such a remote community, not only because the service is much faster, but also significantly more affordable. "Before when we had to buy our bandwidth, it was really, really costly and we could only afford so much. To cover that bandwidth, we had to charge customers a rate probably 50 times higher than in the south, but we'd probably be 100 times slower because of our small population and base of users,'' Ohokannoak says.

In Cape Dorset, in southwest Baffin Island, Jim Williams is taking advantage of broadband access to teach an introductory business course at Fanshawe College in London, Ont. The newly appointed training and development officer with the Government of Nunavut's Department of Community and Government Services moved to Nunavut from southern Ontario in April 2005.

"I was teaching that course when I came up here, and (Fanshawe) asked me if I'd finish it online,'' he says. "When I first came up, we didn't have broadband, and (trying to do) that was awful. You would eventually get through (via dial-up) but it just took so long. Now with broadband access, it's so much easier. You can get back to students right away; it's phenomenal,'' he adds.

In Sanikiluaq, housing foreman Arthur Lebsack of the QAMMAQ Housing Association, who is responsible for inspecting all public housing maintenance in the hamlet, says broadband access to the Internet for such activities as pricing materials has saved him a considerable amount of time inside the office. This, in turn, allows him to get out in the field more to inspect buildings and "take care of the men I'm responsible for.''

The only downside to broadband access, Lebsack jokes, is that it gives him less time to satisfy his caffeine fix. "With dial-up, you could go out for coffee and then come back into the room,'' he laughs.

Broadband access could also potentially enhance the educational experience by allowing for greater online interconnectivity between students in schools within Nunavut and the rest of Canada, as well as for professional development of teachers, according to Murray Horn, Iqaluit based director of corporate services for the Government of Nunavut's Department of Education.

Broadband technology could also allow a specialized teacher based elsewhere to supplement secondary school instruction in a particular subject area such as physics to a remote community, where there might only be a single teacher to cover all subjects and perhaps multiple grades as well, he adds.

"I think we're limited only by our imagination in terms of what we can do with this technology,'' Horn says.

Another important civil application will be to improve municipal operations through shared knowledge. For instance, municipalities within Nunavut often experience a rapid turnover of knowledgeable staff in senior level positions, particularly those that involve southerners, who only tend to stay in Nunavut for a few years. Thus, each new person, particularly in a remote community, tends to "reinvent the wheel because they don't have access to what the other municipalities are doing,'' Thomas says.

"A new senior administrative officer (SAO) in Kimmirut, for example, may have no idea how to handle water truck delivery and sewage management. They'll run into a whole series of problems that other municipalities solved long ago. If they've never done it, how do they connect with other SAOs to figure out how? The way out is to provide training opportunities for people who live there,'' and broadband access will "connect these communities via the Internet in a useful way,'' she adds.

Another potential application in the planning stages is to provide residents of Nunavut with a geo-science software program that will give them satellite images of the Territory, which can in turn be further scaled down in considerable detail. This is especially important in a culture whose traditional activities are intensely land-based, such as hunting and fishing. Moreover, the Inuit people must first be consulted by business and government with respect to proposed commercial activities such as mining or oil drilling because of the potential environmental impact such activities could have on animal migration routes or other matters of importance to their traditional way of life.

For broadband access to ultimately succeed in Nunavut, admits Itorcheak, there will be a nurturing period involving a lot of trial and error and growing pains. "It's like with a newborn, where it takes time to learn to crawl, then to walk, then to run. Eventually people will pick up on it like they did with video and desktop conferencing. You can do a lot of different things, but it will take time,'' he says.

In the process, he adds, it is important that the traditional knowledge of the Inuit culture be respected and not completely trumped by technology. For instance, no matter what computer models say, there is no substitute for the experience of hunters who've passed down oral knowledge about things such as routes to avoid because of ice shifting at various times of the year.

"We've got to incorporate what we've learned about technology into our communication, but at the same time, keep in the back of our minds that we cannot abandon everything we learned from our parents and forefathers. We must also take into account traditional knowledge,'' Itorcheak says.

Saturday, July 16, 2005

Inuit population growing

Canada’s Inuit population still growing fast

By 2017, Inuit population will reach 68,400

Twelve years from now, the face of Nunavut will look much the same as it does today: four out of five residents will be young Inuit.

But there will be more Inuit in Nunavut and across Canada, says a recently-released Statistics Canada report that projects what Canada’s aboriginal population will be in 2017.

Of all the aboriginal populations in Canada, the Inuit population is growing most rapidly. The Inuit population will reach 68,400 in 2017 from 47,600 in 2001.

Only a major economic or climatic change could alter these projections, said the report’s main author.

That’s because Inuit women have a higher birth rate and more children than any other aboriginal group in Canada, the report says.

And fewer Inuit migrate to other regions than other aboriginal groups, says the report, but the main reason for the greater population increase is the high fertility rate among Inuit women.

According to Statistics Canada, by 2017, there will 971,200 Indians, 380,500 Métis and 68,400 Inuit in Canada.

The overall composition of Canada’s aboriginal population would not change significantly. The majority, 68 per cent, would be North American Indian; Métis would represent 27 per cent, and Inuit about five per cent — up from 4.5 per cent in 2001.

The study also says that in 2017:

- Inuit population will still be the youngest of all aboriginal populations in Canada. In 2001 the median age was 20.9. It will be 24 in 2017;

- Inuit children 14 and under will continue to represent a large share of the Inuit population. In 2017, one out of every three Inuit will be under 15;

- Inuit will remain the majority in Nunavut, with 84 per cent of the population;

- Eighty-five per cent of children in Nunavut will be Inuit;

- The number of Inuit children in Nunavut will increase from 9,700 in 2001 to 12,300. “It seems that early education could be a future pressure point,” the report says.

- The number of aboriginal youth in Canada aged 20 to 29 is expected to increase by 40 per cent. This age group is projected to increase to 242,000, more than four times the projected growth rate among the same age group in the general Canadian population.

- The number of aboriginal seniors aged 65 and older could double, although their share of the population would rise from only 4 per cent to 6.5 per cent.

Usually statistical studies cover longer periods of time, such as 20 years or more, but Statistics Canada performed the analysis of information collected in the 2001 census after a request from the Department of Heritage: the federal government wants more information about what Canada will look like on the 150th anniversary of Confederation.

Friday, May 20, 2005

Hunters decry caribou protection decision

- FROM MAY 18, 2005: Wildlife board clashes with minister over caribou designation

Thursday, April 21, 2005

Inuit art advocate James Houston dies

NEW LONDON, CONN. - Canadian artist James A. Houston, who helped introduce Inuit art and culture to the world during the 1950s and 1960s, has died.

Houston died Sunday at Lawrence & Memorial Hospital in New London, Conn., the Day newspaper reported Wednesday. He was 83.

Born in Toronto in 1921, Houston began his study of art early on. At age 11, he studied with the Group of Seven's Arthur Lismer at what is now the Art Gallery of Ontario. He later studied at the Ontario College of Art.

After spending five years serving with the Toronto Scottish Regiment during the Second World War, Houston briefly studied in Paris before deciding to travel to the Canadian Arctic for artistic inspiration. He made his first contact with the Inuit in 1948, when they showed him their carvings. He lived among them for the next 14 years and became a civil administrator for west Baffin Island.

Houston became a major proponent of Inuit arts and culture, introducing stone, ivory and bone carvings created by local artists to the Canadian Guild of Crafts, the federal government, the Hudson's Bay Company and, eventually, the world.

In addition to creating glass and sculptural art, Houston was a documentary filmmaker and author of numerous award-winning novels and children's books about the Inuit people and their stories. His White Dawn was adapted for film in 1974.

For the last 43 years of his life, he worked as a designer at New York City's Steuben Glass Company, where he introduced the use of gold, silver and other precious metals into the company's glass sculptures.

In 1974, Houston was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada for acting as a representative of Inuit artists and craftspeople and, in 1997, the Royal Canadian Geographical Society awarded him its Massey Medal.

In 1981, Houston's son John opened the Houston North Gallery in Lunenburg, N.S. – the province where his mother, Houston's first wife, Alma, who was also an advocate of Inuit art, was born.

According to his wishes, Houston will be cremated, with half his remains to stay with his family in Stonington, Conn., and the other half scattered over the hills of Cape Dorset off Baffin Island.

A memorial celebration is scheduled for May 21 at Mystic Seaport, a historical museum region located 16 kilometres east of New London.

Friday, February 18, 2005

CNN.com - WWF: Chemical waste�polluting�Arctic - Feb 18, 2005

Thursday, February 03, 2005

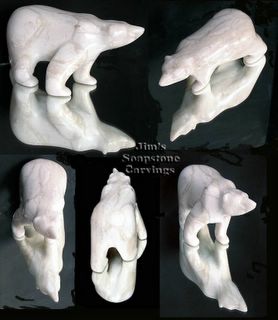

Musk Oxen Sculpture

Stunning Musk Oxen sculpture 'Tenacity' 16 inches long, one piece of soapstone with horns carved from genuine Walrus tusk.

SOLD

Sculpture by Jim

http://www3.sympatico.ca/ve3jji

Polar Bear sculpture

Arctic Ozone Hole

Last Updated Tue, 01 Feb 2005 18:56:23 EST

CBC News

IQALUIT - Unusually cold temperatures above the Arctic could cause a record loss of ozone over the Arctic this year, increasing the danger from ultraviolet radiation, European scientists warn.

Temperatures in the stratosphere – about eight kilometres above the Earth's surface – have plunged much lower than normal in the last two months and the ozone layer that shields the planet is already being affected, the European Commission scientists say.

Widening holes in the ozone layer could let more UV radiation hit bears and other creatures in polar regions.

Ozone depletion is usually blamed on chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, but scientists are pinning this year's loss on unusual cloud formations caused by the frigid weather.

"We get a lot of these polar stratospheric clouds forming, but the problem is they accelerate, or lead to ozone depletion," said Dr. Neil Harris of Cambridge University in England, who heads the international team of scientists monitoring the ozone layer.

If the subnormal temperatures continue until spring, it could lead to the biggest loss of ozone in more than 50 years, Harris warned.

"That's the big 'if' here," he said. "But if it stays cold – and there's no sign of it warming up in our 10-day forecasts – then these large losses are very likely to happen.

"At particular altitudes, it would be 50, 60, 70 per cent."

Harris said the greatest loss in ozone would likely occur above the Arctic Circle, posing more health hazards for people and animals there. They're already exposed to higher than average ultraviolet radiation, which has been linked to a rise in some types of skin cancer.

While there's a debate over what caused the low temperatures, Harris is one of many scientists who blame global warming.

"Just as the polar regions are probably most affected by climate change at the ground, there may well be a strong link in the upper atmosphere, as well."

Monday, December 27, 2004

Nunavut woman reaches South Pole

Last Updated Fri, 24 Dec 2004

SOUTH POLE - A Nunavut woman and her two grown-up children reached the South Pole on Thursday after a trek of nearly 1,100 kilometres, setting a new record along the way.

Matty McNair, a U.S. citizen who makes Iqaluit her home, became the first female resident of Canada to reach the South Pole on foot without help when her team reached the bottom of the world at about 3 p.m. EST on Thursday.

"I feel exhilarated and exhausted both," said McNair.

McNair made the 1,085 km trek from Hercules Inlet on the edge of Antarctica to the Pole with her children Eric and Sarah Landry, 20 and 18 respectively.

The group, which also included British couple Conrad and Hilary Dickinson, set out on skis Nov. 1, dragging their supplies on sleds and received no help along the way.

"I cannot believe we're here. It still amazes me and it's been such an incredible journey to do this with my kids," said McNair, who in 1997 led the first women's expedition to the North Pole.

From the South Pole, the team plans to set another record in their return to Hercules Inlet, making their expedition the longest foot journey on the southern continent.

They hope to make the return trip in 25 days by using kites to pull them across the ice.

Monday, December 20, 2004

Inuit Climate rights

BOB WEBER

(CP) - A Canadian-led international Inuit group is beginning legal procedures to convince a major international organization that global warming violates their human rights.

"The destruction of Inuit hunting culture through climate change caused by emission of greenhouse gases is a violation of the human rights of Inuit," said Sheila Watt-Cloutier, president of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference. "This is rather new to the international world, but I think we're breaking new ground here."

Speaking from Buenos Aires, Argentina, where she was to address a UN-sponsored conference on climate change Friday, Watt-Cloutier said her group will ask an arm of the Organization of American States to rule on the issue.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has no enforcement power. But a ruling in favour of the Inuit could bolster their case - especially against countries such as the United States, which have signed on to the Organization of American States but have been reluctant to take action against climate change.

"Because they signed on, they have assumed certain obligations they must uphold, and the commission and international law have shown that those obligations translate into respect for human rights," said Paul Crowley, lawyer for the Inuit group, which represents 155,000 Inuit around the world.

"We're looking at what may be a small jump, but a jump that is ready to be made, in terms of environmental security and international law and international human rights."

Crowley said a positive ruling from the commission, which has been in existence since 1948, would give the Inuit a greater presence and voice at international conferences.

"It is a well-respected commission that does make decisions that enter into the body of international law," he said.

"You win in terms of credibility into global negotiations such as those that are happening here."

Crowley noted that out of the two weeks of discussion at the current UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, only a few three-minute blocks were given to aboriginal groups to explain how they are being affected by global warming. The Inuit Circumpolar Conference was given one of those blocks.

The petition to the Inter-American Commission will take a while to complete, Crowley said. Interviews in Inuit communities will be conducted this winter and the document could be ready by the spring.

Watt-Cloutier, a Canadian who lives in Iqaluit, said studies suggest the Inuit way of life could be wiped out by global warming.

"Here we are, Inuit of the world who have lived in harmony with our surroundings, and we're being bombarded by toxins," she said.

"Now our climate and our environment is being impacted. What recourse do we have to tell the world to stop?"

© The Canadian Press, 2004

Thursday, September 30, 2004

The Legend of the Giant

“In the land of the Inukjuangmiut there once lived a giant who captured an Inuit hunter and carried him off inland

on his back. It was a long journey and the hunter contrived by various means to tire his captor so that the time

came when the giant was forced to lie down and rest. Once he was asleep, the hunter saw his chance, hacked

off the giant's head and made his escape.

But the giant's wife gave chase and caught up with the hunter. When she struck out at him he dodged behind

a rock and her blow smote the rock, splitting it in two. From the crack poured a mighty torrent of water that soon

formed a river. The woman, exhausted from the chase, stopped to drink from it and drank so much that she burst.

Thus did the Inuit hunter overcome his enemies and return to his family.

The river, which flows to this day, is called Inukjuak – the Giant. The settlement at it's mouth takes the same name

and those who live there are known as Inukjuangmiut – the People of the Inukjuak”.

Sunday, September 26, 2004

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part L

Native American Recipe

Boiled Salmon-Guts

Mestag.ilaku

After the woman has cut open the silver-salmon caught by her husband by trolling, she squeezes out the food that is in the stomach, and the slime that is on the gills. She turns the stomach inside out; and when she has cleaned many, she takes a kettle and pours water into it.

When the kettle is half full of water, she puts the stomach of the silver-salmon into it. After they are all in she puts the kettle on the fire; and when it is on the fire, she takes her tongs and stirs them. When (the contents) begin to boil, she stops stirring. The reason for stirring is to make the stomachs hard before the water gets too hot; for if they do not stir them, they remain soft and tough, and are not hard. Then the woman always takes up one of (the stomachs) with the tongs; and when she can hold it in the tongs, it is done; but when it is slippery, it is not done.

(When it is done,) she takes off the fire what she is cooking. It is said that if, in cooking it, it stays on the fire too long, it gets slippery. Then she will pour it away outside of the house, for it is not good if it is that way.

If it should be eaten when it is boiled too long, (those who eat it) could keep it only a short time. They would vomit. Therefore they watch it carefully. When it is done, the woman takes her dishes and her spoons, and she puts them down at the place where she is seated; but her husband invites whomever he wants to invite.

When the guests come in, his wife takes a large ladle and dips the liquid out of the kettle into the dishes. When they are half full of the liquid of what she has been cooking, she takes the tongs and takes out the boiled stomachs and puts them into the dishes. When all the dishes are full, she takes food-mats and spreads them in front of the guests. Finally she takes the dishes and places them in front of the guests. There is one dish for every four guests. Then she gives a spoon to each guest.

Water is never given with this, and they never pour oil on it, for oil does not agree with the boiled stomach; and therefore also they do not drink water before they eat it, for it makes those who eat it thirsty. Then they eat with spoons; and after they have eaten, the host takes the dishes and puts them down at the place where his wife sits.

Then he takes water and gives it to them. Then they rinse their mouths on account of the salty taste, for the boiled stomach is really salt. After rinsing the mouth, they drink some water; and after drinking, they go out of the house.

This finishes what I have to say about the cooking of various kinds of salmon. They never sing when eating steamed salmon-heads or boiled salmon-heads, or when they eat boiled stomachs, for these are eaten quickly when they first go trolling silver-salmon.

The stomach of the dog-salmon is not eaten when it is first caught at the mouth of the river, nor when it is caught on the upper part of the rivers; but they boil the heads when it is caught in the upper part of the river, also those of the humpback-salmon. At last it is finished.

Boiled Salmon-Guts

Mestag.ilaku

After the woman has cut open the silver-salmon caught by her husband by trolling, she squeezes out the food that is in the stomach, and the slime that is on the gills. She turns the stomach inside out; and when she has cleaned many, she takes a kettle and pours water into it.

When the kettle is half full of water, she puts the stomach of the silver-salmon into it. After they are all in she puts the kettle on the fire; and when it is on the fire, she takes her tongs and stirs them. When (the contents) begin to boil, she stops stirring. The reason for stirring is to make the stomachs hard before the water gets too hot; for if they do not stir them, they remain soft and tough, and are not hard. Then the woman always takes up one of (the stomachs) with the tongs; and when she can hold it in the tongs, it is done; but when it is slippery, it is not done.

(When it is done,) she takes off the fire what she is cooking. It is said that if, in cooking it, it stays on the fire too long, it gets slippery. Then she will pour it away outside of the house, for it is not good if it is that way.

If it should be eaten when it is boiled too long, (those who eat it) could keep it only a short time. They would vomit. Therefore they watch it carefully. When it is done, the woman takes her dishes and her spoons, and she puts them down at the place where she is seated; but her husband invites whomever he wants to invite.

When the guests come in, his wife takes a large ladle and dips the liquid out of the kettle into the dishes. When they are half full of the liquid of what she has been cooking, she takes the tongs and takes out the boiled stomachs and puts them into the dishes. When all the dishes are full, she takes food-mats and spreads them in front of the guests. Finally she takes the dishes and places them in front of the guests. There is one dish for every four guests. Then she gives a spoon to each guest.

Water is never given with this, and they never pour oil on it, for oil does not agree with the boiled stomach; and therefore also they do not drink water before they eat it, for it makes those who eat it thirsty. Then they eat with spoons; and after they have eaten, the host takes the dishes and puts them down at the place where his wife sits.

Then he takes water and gives it to them. Then they rinse their mouths on account of the salty taste, for the boiled stomach is really salt. After rinsing the mouth, they drink some water; and after drinking, they go out of the house.

This finishes what I have to say about the cooking of various kinds of salmon. They never sing when eating steamed salmon-heads or boiled salmon-heads, or when they eat boiled stomachs, for these are eaten quickly when they first go trolling silver-salmon.

The stomach of the dog-salmon is not eaten when it is first caught at the mouth of the river, nor when it is caught on the upper part of the rivers; but they boil the heads when it is caught in the upper part of the river, also those of the humpback-salmon. At last it is finished.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part K

Still, if cooperation remained an important value for most families in the 1950s and early 60s, the increased geographical mobility of village residents reduced the opportunity for its active expression. In families where traditional subsistence pursuits were regularly followed, expectations regarding labor exchange, borrowing, and sharing continued to be reinforced. Men hunted together and shared their catch. Women assisted each other with baby tending, carrying water, and similar household-related responsibilities. Members of related families helped each other too, constructing, repairing, and painting houses, borrowing another's boat, sled or dogs, and sharing the use of electric generators. However, as more individuals left their communities for seasonal or year-round employment elsewhere, this cooperative pattern became steadily harder to follow.

By the mid-1960s, seasonal migration was evident in all Arctic villages. Men left home for summer jobs as soon as spring seal hunting was over in early June. Many sought jobs in central and southern Alaska, or at one of the numerous military sites scattered throughout the newly-formed State. Often they were hired as common laborers or cannery workers, although a few became skilled carpenters, heavy equipment operators, fire fighters, and mechanics. Those joining a union found summer jobs through the employment office in Fairbanks, thereby enabling them to leave directly for their work site. Working "outside" also brought expections that at least part of the wages would be sent home, an arrangement that was upheld by older married men far more often than by younger single adults.

In other villages like Barrow and Kaktovik, jobs were available locally. But even here, the nature of the work left men inadequate amounts of time to engage in subsistence hunting and fishing. Working a six-day week, few individuals could give more than minimal assistance to others and therefore, could expect little in return. With sufficient cash income to purchase most of their food and other required goods, it might have been possible to share these items with the fulltime hunter in exchange for fresh meat, fish, and other traditional food products. But this modern version of reciprocal exchange was unusual, and the transaction most often occurred through the medium of the village Native store.

Many Inupiat expressed great concern over this turn of events; on the one hand wanting the material advantages of a good cash income, and on the other, disliking the penalty that it seemed to require. As the importance of the extended family continued to decline, further reductions in the traditional patterns of cooperation occurred. Could the expression of this value find another institutional base outside the extended family? Non-kin based institutions carrying the greatest meaning for the majority of adult Inupiat were the Christian churches. Here, members contributed freely of their time and energy in support of numerous religious activities ranging from weekday services and mother's club meetings to summer bible schools. Similar efforts were put into the maintainance of church buildings, missionary residences, and the like. But few thought such collective endeavors could replace the deteriorating cooperative ties linking families and generations together.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part J

While these comments reflect an especially strong alienation derived in large part from his acceptance of Euro-American stereotypes learned during his life in the "States," many youths in the 1960s showed lessened regard for old Inupiat ways; and after leaving home, simply ignored the traditional pressures to conform. When their actions disrupted village life, as was the case of individuals who became aggressive after drinking, they might be brought before the village council. But the effectiveness of the council as a deterrent depended largely on the prestige of the councilors, their previous experience, the type of problem brought before them, and the degree of support given by local Whites.

A few village councils such as the one at Point Hope were organized as early as the 1920s when they were encouraged by resident missionaries. But at best they were only nominally effective. The only significant legal authority they had was the ability to file a complaint with the U.S. Marshall. The major impetus for the development of local self-government - Euro-American style - on the North Slope came in the mid-1930s after governmental responsibility for the Inupiat had been placed under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs; although one or more councils were organized as early as the teens farther south in the Kotzebue area. With the passing of the Indian Reorganization Act [IRA], the Inupiat and other Native Americans were urged to draft village constitutions and bylaws, ratify them by majority vote, and submit them for approval to the U. S. Secretary of the Interior.

By 1960, all Inupiat villages with a population of 100 or more had some form of self-government. Most were organized formally with an elected president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer, and several councilors. They met at regular intervals and took action on such common problems as supervising the operation of Native cooperative stores, spring village cleanup, promoting civic improvements, and making and enforcing local regulations. In every instance, elected officials were Inupiat men.

One difficult problem facing the councilors was that of coordinating community activity, such as village cleanup. Not only did these village leaders have to contend with lack of precedent, but they had to be careful not to identify themselves too closely with White power figures for fear that other village members would conclude they no longer represented Inupiat needs and interests. Leaders who ceased sharing the norms, objectives, and aspirations of the larger group ceased being leaders. Nor could they assume an authoritarian or aggressive stance in their actions for such behavior went directly against traditional Inupiat values.

An illustration of how these factors resulted in the replacement of a village leader at Point Hope is reflected in the efforts to build a community-wide electric power plant. Most local residents were in favor of obtaining a power plant, but they had little knowledge of how to implement such a plan. Nevertheless, with the urging of the council president, arrangements were made and the plant constructed. Problems arose immediately, most of them linked to monthly charges each family had to pay for electricity. Locally designated "bill collectors" refused to press for these payments, at which point the council president, faced with the possibility of backruptcy, aggresssively reminded the villagers of what happens to White Americans who refused to pay their bills. Although the installation of meters eventually resolved the immediate financial problem, this leader lost much of his influence and was not re-elected to the council. Similar problems emerged elsewhere at this time as the primary qualification for election to village councils began shifting from older prestigous community leaders who had the respect of the community to younger, more educated, individuals who had the ability to speak and write good English, but little other knowledge or experience.

But it was in the area of law enforcement that the councils faced their greatest dilemma. Having established regulations against the importation of intoxicating beverages, the members had no way of enforcing their rulings. The same problem occurred with gambling, curfews, and the confinement of dogs. With the exception of Barrow, by 1960, no community had obtained sufficient funds to hire an outside law enforcement officer - and few local local Whites, even if requested, had any interest in becoming involved in such a responsibility.

When an individual disregarded a local regulation, he or she was usually approached by a council member, reminded of the ruling, and told to conform. If the individual persisted, the person was brought before the council and asked to account for the behavior. This practice was most effective with village youths, but was pursued with adults as well. For more serious offenses like minor theft, a combination of council and family pressures would be applied to the offender who was usually a teenager. Before the 1960s, theft was uncommon among the Inupiat, and adults spoke of this misdemeanor with strong feelings of indignation. However, by this time the problem had become of sufficient concern that in most Arctic villages, householders locked their doors on leaving home for any length of time.

The issues which the councilors were the least able to resolve concerned drinking and the curfew. Although liquor was forbidden by local ordinances, the moderate drinkers were seldom criticized as long as they indulged in the quiet of their own homes. Beer and alcohol were obtained by air freight from Fairbanks, through a resident White, or from a friend recently returned from the "outside." Drinking was considered a problem when it resulted in such open hostility as destruction of property, picking a fight, or wife-beating. There were also instances of young Inupiat who under the influence of liquor, killed the lead dog of another hunter, destroyed furniture and other household items, and broke into government buildings for purposes of theft. Generally, under such circumstances, public opinion did not support taking firm sanctions against the offender. This was largely due the Inupiat perception that those who drank were not responsible for their actions - and thus, couldn't be held accountable. That is, "being drunk" was not only an explanation for damaging behavior, it was also a justifiable excuse.

Given this increase in social problems, the Inupiat remained committed to a common set of cooperative standards covering a wide range of behavior, and, with relatively few exceptions, actively conformed to these standards. In the villages, there was no overall sense of lawlessness, no rampant vandalism, delinquency, crime, sexual misconduct, or alcoholism.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part I

Traditional Inupiat society has always characterized as having few social institutions beyond the family. Thus, in many respects, settlements and villages represented a community of interest rather than a corporate unit. Since there was no political organization, various social sanctions, customary law, common goals and norms had to provide the essential fabric of settled life. Individuals had great freedom of choice in their actions, but their security lay in cooperating and sharing with one another.

Nonconforming individuals, such as an aggressive bully or persistent womanizer, presented a continual problem in these localities. If nonconformists could not be curbed by the actions of kin or the force of public opinion, the one remaining alternative was to exclude them from participation in the community's economic and social life - a rather effective sanction given the unpredictable conditions of Arctic life. If severe interpersonal conflicts arose between one or more members of different kin groups, the villagers were faced with a serious dilemma, for there was no available technique for resolving feuds once they had begun. It was not until long after the government had assigned U.S. marshals to police this northern area that interfamily feuds resulting in bloodshed disappeared entirely.

As long as Inupiat economic and social security depended on the assistance and support of others, gossip, ridicule, and ostracism was quite effective in ensuring conformity to group norms. Inupiat socialization, emphasizing as it did rapid fulfillment of the child's needs and wants, freedom of action in many spheres, early participation in adult-like responsibilities with appropriate recognition for achievement, and the rejection of violence in any form, also encouraged the formation of a conforming rather than a rebellious personality type. However, this method of social control was considerably weakened when family groups became less cohesive, when greater opportunities for wage labor brought increased economic independence, and when substantial value conflicts began occurring between generations. All these trends had become fully developed by the early 1960s.

Given these changes, it was hardly surprising that traditional mechanisms of social control soon lost much of their effectiveness. One teenager from Barrow summed up this perspective in his comments on the strict curfew in effect at Wainwright in 1961:

When I visited the village, I didn't know about the midnight curfew for young people. I went out until about three in the morning with a local girl. I went out late the next night and on the following day a village council member spoke to me at the post office about the curfew. I told him I was a visitor from Barrow and I shouldn't have to obey the curfew. He said I did, but I kept going out late anyway. Finally, the whole council called me in and told me I could not go out after twelve o'clock anymore, and I said, "This is America, not Russia and I can go out as much as I like." The council didn't like that, but there was nothing they could do. I left soon afterwards, though. That Wainwright is a strict place.

After a similar visit to Kaktovik, this same youth gave further insight into the reasons behind his negative attitude toward the more isolated Inupiat villages:

After living in the States, I can't stand this place for very long. The people here, they don't know what it is like outside. Some of the boys brag about how good they are, but I just keep quiet, laughing inside. They haven't seen anything like I have. And another thing, they don't have any respect for privacy. Why, they just come into your house without being invited and drink your coffee, or anything. The people at Barrow don't do things like that. They have much better manners and aren't so backward.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part H

Finally, they came back up and the man saw an igloo along the edge of the ice pack. Then went inside and the man saw another bear with a spear in his haunch. The first bear said, "If you can take that spear out of the bear and make him well, you will become a good hunter." The man broke off the shaft, eased the spear point out of the bear's haunch, and the wound began to heal. Then the first bear took off his bearskin "parka" and became a man. After the wound was healed completely, the bear-man put back on his bearskin "parka," told the poor hunter to climb on his back and close his eyes, and together they went back into the sea. When the bear finally stopped, he asked the man to open his eyes. Looking around, the man realized he had been returned to the spot from which he began his journey. He thought he had only been gone a day, but on arriving home, he found that he had been away a month. From then on, the man was always a good hunter.

In this, as in many other myths, spirits of animals represented the controlling powers. Essentially, the Inupiat perception of the universe was one in which the various supernatural forces were largely hostile toward human beings. By means of ritual and magic, however, the Inupiat could influence the supernatural forces toward a desired end - be it influencing the weather and food supply, ensuring protection against illness, or curing illness when it struck. The power to influence these events came from the use of charms, amnulets, and magical formulas, observance of taboos, and the practice of sorcery.

Although all individuals had access to supernatural power, some were considered to be especially endowed. With proper training, these individuals could become a practicing shaman, or angatqaq. The Inupiat angatqaq was a dominant personality and powerful leader. Due to their great intimacy with the world of the supernatural they were considered particularly well qualified to cure the sick, control the forces of nature, and predict future events. At the same time, they were also believed to have the power to bring illness, either to avenge some actual or imagined wrong, or to profit materially from its subsequent cure.

The Inupiat of this region traditionally saw illness as resulting from one or two major causes: the loss of one's soul or the intrusion of a foreign object. A person's soul could wander away during one's sleep, be taken away by a malevolent shaman, or leave because the individual failed to follow certain restrictions placed on her or him by a shaman or the culture in general. Illness caused by intrusion was usually the work of a hostile shaman, but in either case, an effective cure for a serious illness could only be achieved through the services of a competent Native curer.

Although shamans had extensive powers, lay Inupiat were not without their own sources of supernatural influence. By means of various songs, charms, magical incantations, and even names, individuals could ensure the desired end. The acquisition of these instruments of supernatural power came through inheritance, purchase, or trade, with charms and songs changing hands most easily and often. The major difference between the shaman and the lay Inupiat was the greater degree of supernatural power assumed to be held by the former. The shaman did have one particular advantage, however - access to a tuungaq - or "helping spirit." Similar to the concept of guardian spirit found throughout many Native American groups, the tuungaq was commonly an animal spirit, often a land mammal that could be called upon at any time to assist the shaman. When it was to the shaman's advantage, it was believed that he might turn himself into the animal represented by the spirit.

The influence of the shaman began to decline following the arrival of White whalers who, without regard for the numerous taboos rigidly enforced by the Inupiat shamans, consistently killed large numbers of whales. Native converts to Christianity, holding the bible aloft, also flaunted traditional taboos without suffering, By the early 1960s, shamanism was rarely if ever practiced in northern Alaska. This does not mean, however, that individuals once known to be shamans, or capable of becoming shamans, were ignored. On the contrary, the Inupiat felt quite uneasy about such people.

At this time, the Presbyterian, Catholic, and Episcopal churches on the North Slope had been joined by several new denominations including the Assembly of God in Barrow and Kaktovik and, to a lesser extent, the Evangelical Friends in the area of Point Hope. All of these church groups stressed the efficacy of prayer - that is, the immediate intervention of God in daily affairs. This intervention was usually asked in two major areas: hunting and health. The churches preached that God could heal directly, although the evangelical churches put forward this doctrine more forcefully. Presbyterians, for example, used prayer as a supplement to medicine whereas the Assembly of God members frequently reversed the emphasis. In the Presbyterian church, the minister or congregation as a whole might be asked to pray for an ill member. In the Assembly of God church, any small group of members regardless of status were commonly called upon to help "lay on [healing] hands" when someone was sick.

Prior to the arrival of the evangelical missionaries, each village had one established church. There is little question that the homogeneity of religious belief arising from this arrangement encouraged a sense of identity within the village as well as with the Judeo-Christian world. Regular services brought together most village residents in a common ritual. The establishment of local church offices provided a structure for the emergence of new leaders. And a common doctrine set a standard by which Inupiat could measure their own religious and moral behavior. So too, resentment against others within our outside the community found expression in the act of refusing to attend church - an action that was quite effective since attendance at that time was one of the few activities expected of all village residents. Only salaried employees could be considered exempt, and even then, the more religious felt considerable qualms about working on the Sabbath.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part G

Following a period of general relaxation, informal conversation, and further serving of meat and tea, the nalukatak skin ["skin for tossing"] was brought out. Of all the Inupiat ceremonial customs, the nalukatak or "blanket toss" is probably the most well known to Euro-Americans; and it was an exciting event to watch.

After bringing out a skin [made by sewing numerous walrus hides together], thirty or more Inupiat took their places in a circle, grasping firmly with both hands the rope handgrips or rolled edge. The object of the game was to toss a person into the air as high as possible - sometimes reaching more than twenty feet. Such people were expected to keep their balance and return upright to the blanket. Especially skilled individuals might do turns and flips. Usually the first to be tossed were the successful umialit. In earlier days, while high in the air, they were expected to throw out gifts of baleen, tobacco and other items to the crowd. More recently, candy has been used as a substitute. Once an individual lost her or his footing, another took a turn until all had a chance to participate.

In the late afternoon or evening, a dance was scheduled. When a permanent dance floor or temporary board platform had been made ready, five or ten male drummers, supported by a chorus of men and women, announced the beginning of the dance. The first dance, called the umialikit, was obligatory for the umialik, his wife and crew. All other crew members then danced in turn, followed by other men and women in the village. The affair usually lasted well into the night.

Christian and national holidays, including Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year's Day, Easter, and Independence Day, were actively celebrated by the Inupiat as well.

At this time, contradictions between traditional Inupiat beliefs and those of Christianity were given little direct attention. Most adult villagers considered themselves to be staunch supporters of Christianity. But they also held other beliefs that they knew EuroAmericans didn't share - and thus were cautious about discussing them with outsiders.

One way to learn about earlier Inupiat religious beliefs was to ask the elders to relate legends that had passed down from generation to generation. A well-known story shared by an elderly Barrow resident illustrates the animistic nature of Inupiat religion:

Once there was a poor hunter. He always went out but never got anything. Finally, one day he saw a polar bear. As he crawled toward it over the ice, the bear said to him, "Don't shoot me. If you follow me and do what I say, I will make it so you will always be able to get whatever animals you think about." The bear told the man to climb on his back and close his eyes. "Do not open them until I tell you to." Then, the man and the bear went down into the sea a long way. "Do not open your eyes," the bear reminded him.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part F

All Inupiat children from six to sixteen were required to attend local Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA] schools. Parents generally agreed that school was a necessary part of the modern child's education, and children themselves enjoyed the contrast of school and home. Still, the themes addressed in the classroom differed markedly from those of everyday Inupiat life, and many a youth would have preferred lessons in hunting and skin sewing to those in arithmetic, geography, social studies, and English. Nor did they see much benefit in following newly arrived BIA teachers admonitions that they learn to "Be prompt," Work hard to achieve success," Learn the values of banking and budgeting," and particularly "Keep clean," for such middle class American values had little meaning for life at home.

Although the core of aboriginal Inupiat life centered around the nuclear and extended family, the relationship was continually reinforced by patterns of mutual aid and reciprocal obligation. Beyond the immediate circle of kin, there existed additional social groups, some of which were kin-based and others which were not. Joking partners, for example were usually cross-cousins. Hunting partners were often related, though not always. The qargi club houses, primarily used by extended families for educational and ceremonial purposes, also served as socializing centers for unrelated others. In the large whaling community of Barrow, there were once three qargit, each linked with a whaling captain [umialik] and his crew, although additional family members and their wives were not excluded. It was through participation in institutions such as the qargi that the Inupiat developed a larger sense of identity with a particular locality or settlement.

At one time, the qargi was the meeting place of one of the most important aboriginal festivals held on the North Slope - the Messenger Feast. Usually organized in December, it was a ceremony with both social and economic significance. In early winter, an umialik of a given settlement sent messegers to a nearby locality to invite its residents to participate in an economic exchange. Because of the effort that had to be expended, no one group could afford to give such a feast each year. The choice of the invited settlement was based on the number of trading partners involved and the length of time lapsed since the previous invitation. Elaborate gift exchange between residents added to the development of inter-community solidarity, as did the opportunity for distant kin to re-establish social and economic ties while participating in the activities of the feast.

By the early 1960s, neither the qargi ceremonial centers nor the Messenger Feast were significant community institutions on the North Slope. No qargi remained at Barrow or Wainwright, and at Point Hope the two qargit were only meaningful in so far as they affected the patterning of the Christmas and spring whaling feasts. Similarly, only a vestige of the Messenger Feast was held between Christmas and New Year's Day.

The one important traditional ceremony still actively participated in through the 1960s [and continuing to the present] was the nalukatak, or spring whaling festival. Arrangements for this celebration, which took place at the end of the whaling season, were made by the successful umialiks and their families. If no whales were caught, there was no ceremony. Formerly, the festival took place in the qargi of the successful umialik. One of its purposes was to propitiate the spirits of the deceased whales and ensure through magical means the success of future hunting seasons. A modern adaptation of this religious belief is seen on those occasions when Christian prayers of thanksgiving are recited during the ceremony.

On the day chosen for the event, every boat crew that had killed one or more whales during the season hauled their umiaq out of the sea and dragged them to the ceremonial site. The boats were then turned on their side to serve as windbreaks and temporary shelter for the participants, and braced with paddles or forked sticks. Masts were erected at the bow and from the top were flown the small bright-colored flags of each umialik. Before Christian teaching changed the practice, the captain placed his hunting charms and amulets on these masts. When the site had been arranged completely and a prayer given, the families of the umialik cut off the flukes and other choice sections of a whale, and distributed them along with tea, buscuits, and other food to all invited guests.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part E

Young girls, and to a lesser extent young boys, learned techniques of butchering while on hunting trips with older siblings and adults. In most instances, however, neither girls nor boys became at all proficient in this skill until their late-teens or early twenties. Prior to complusory school attendance and the hospitalization of large numbers of youths for tuberculosis, such knowledge was attained at an earlier age. A girl, especially, learned butchering as a young teenager since this skill was essential in attracting a good husband. But by the 1960s, it was more likely to be picked up after marriage - and not always then.

Siblings played together more happily than is often the case in American society, but sibling rivalry was not completely absent. Hostility was generally expressed by tattling or engaging in some form of minor physical abuse. However, anyone indulging in hard pushing, elbowing, pinching, or hitting was told immediately to stop. Rather than fight back, the injured party was more likely to request help from an older sibling or near adult. Verbal abuse was also rare.

By contrast, competiveness, derived from pride of achievement or skill attainment, characterized many children's activities. In games involving athletic prowess, a child would say, "Look how far I can throw the stone," rather than "I can throw the stone farther than you." When rivalry was more direct, it was expected that the game be undertaken in good spirit and the skills of one participant not be flouted at the expense of the other. Aggressive competitiveness was explicitly condemned, as when a father childed his son, "Why you always wanting to win?"

Only very young children limited their play to those of like age. After reaching five or six, the age range of playmates widened considerably. Team games such as "Eskimo football," were particularly popular and had as participants children of both sexes ranging in age from five to twelve. The game combined elements of soccer and `keepaway,'and when played by older boys, elements of rugby as well. It was not until adolescence that a young person actively set herself or himself apart from other children. Youths of this age group briefly watched youngsters play volleyball or some other game, but seldom participated. Adults encouraged this separation, and when they saw a teen-age boy or girl playing with younger children, they would say, "That person is a little slow in his [or her] development."

Many other popular games were played as well. Some, involving feats of skill and strength such as hand wrestling, have had a long history among the Inupiat. Others such as kick-the-can, volleyball, and board games like monopoly and scrabble, were introduced by Whites. Still other games combined elements of both. Haku, an Inupiat team game in which the object was to make the members of the opposite team laugh, included the offering of amusing portraits of Hawaiian and Spanish dances, done, if possible, with a straight face. A few traditional Inupiat games like putigarok, a form of tag where the person who was "it" tried to touch another on the same spot on the body in which he or she was tagged, closely resembled the western game of tag. Some children occasionally played a fantasy game called "polar bear" in which one child took the role of an old woman who fell asleep. The polar bear then came and took away her child. She then woke up and attempted to discover where the bear had hidden it. At Barrow, Inupiat children played a slightly different version of the same game called "old woman." A youth played the role of an old woman who pretended to be blind. When several of her posessions were stolen, she "accused" other children of taking them. This game required a fair amount of verbal exchange. The more able the talker, the more likely the winner. Story telling was one of the most popular forms of Inupiat entertainment, especially during the winter months when outside activity was sharply diminished. Typical stories involved autobiographical or biographical accounts of unusual incidents, accidents, hunting trips, or other events deemed interesting to the listener. Following the evening meal, a father might call all the children around him and recount his last whale hunt, or how he shot his first polar bear. A good storyteller acted out part of the tale, demonstrating how he threw the harpoon at the whale's back, or how the bear scooped up the lead dog and sent him flying across the ice. Other stories told by other people described life long ago before the tanniks arrived. Myths and folk tales portrayed exploits of northern animals and birds endowed with supernatural qualities.

Children, too, liked to tell stories to each other. These short tales usually described some recent activity, real or imagined. Young Inupiat were passionately fond of horror stories, and a vivid description of raw heads and bloody bones quickly elicited delighted screams of fear from the throats of the listeners. If the teller acted out part of the story, so much the better.

The Inupiat child's creative imagination was reflected in all the activities of story telling, imitating others, playing store, and inventing new games. Young girls turned a bolt of cloth into a regal gown which they wore to an imaginary ball. Boys of four or five climbed under a worn blanket with make-believe airplanes to practice night flying. Charging over the tundra with sharply pointed sticks, a pair of six year olds cornered their supposed furry opponent. This kind of spontaneity, supported by flexible routines and a minimum of rules, continued until the early teens when events of the real world began to offer greater challenges. Only in the confines of the classroom did these children find their psychic freedom curtailed.

The Inupiat of Northern Alaska Part D

A youngster who wined, sulked, cried, or expressed some other unacceptable emotion, was told flatly, "Be nice!" If it appeared to be getting into mischief, it was warned, "Don't pakak!" There were other frequently offered admonitions as well: "Don't ipagak! meaning do not play in the water or on the beach; "shut the door," to keep out the cold; "Put your parka on," guaranteeing adequate dress for outside; "Don't go in someone else's house when no one is at home," reflecting concern for others' property. Most common was "Don't fight!" which was directed not only against personal assaults and rock throwing, but also verbal quarrels.

A child's reaction to any of these treatments ranged from compliance, temporary fears, or unhappy looks - all of which were usually ignored - to sulking, rebellious shrieks, or silent resistance. This latter took the form of ignoring orders or repeating the behavior to see if the adult would take notice. It was rare indeed to hear a child talk back, verbally refuse to perform the action, or say petulantly, "I don't want to." Sometimes a child did threaten vengence - when it was angry at another child or an outsider such as a tanik - but it was most unusual to hear threats directed at parents or adult relatives. By adolescence, discipline seemed to consist entirely of lectures, though still delivered in the harsh tone characterizing Inupiat cautions.

After the age of five, a child was less restricted in its activities in and around the village although walking on the beach or ice still required an adult. During the dark winter season, the child remained indoors or stayed close to the house to prevent it from getting lost and to protect it from polar bears which occasionally entered a village looking for food. In summer, children played at all hours of the day and "night," or at least until their parents went to bed.

By the eighth year, some of the responsibility for a child's socialization had been passed from adults to peers. Children frequently lectured each other using the same admonitions as told to them earlier: "Don't fight," "Don't pakak," "You supposed to knock," and "Shut the door." Rule-breaking might also be reported to a nearby adult: "Mom. Sammy ipagak." Tattling was not depreciated to the extent that it had once been. Still, while older children regularly "played parent" in which they imposed adult rulings on younger ones, all children instructed each other irrespective of their age. Such instruction was generally taken in good spirit. Thus, when an younger child reminded an older one, "You supposed to knock," the latter was likely to smile sheepishly, go out of the room, knock, and enter again.

Although not burdened with responsibility, boys and girls were both expected to take an active role in family activities. In the early years, these were shared, depending on who was available. Regardless of gender, it was important for a child to know how to perform a wide variety of tasks and give assistance when needed. Both sexes collected and chopped wood, got water, helped carry meat and other supplies, oversaw younger siblings, ran errands for adults, fed the dogs, and burned trash. As children grew older, more specific responsibilities were allocated according to gender. Boys as young as seven might be given an opportunity to shoot a .22 rifle, and at least a few boys in every village had taken their first caribou by the time they were ten or eleven.

|

|